Mesopotamia is the ancient Greek name (meaning “the land between the two rivers”, Tigris and Euphrates) for the region corresponding to present-day Iraq and parts of Iran, Syria and Turkey. It is considered the “cradle of civilization” for many inventions and innovations that first appeared here c. 10,000 BC until the 7th century AD.

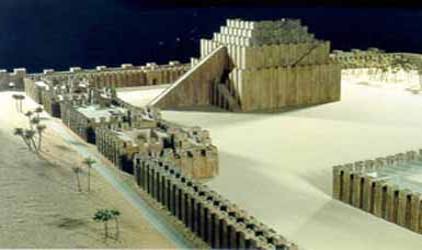

In the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period, humans gradually moved from a hunter-gatherer paradigm to an agrarian one, forming seasonal communities that became permanent during the Ceramic Neolithic (c. 7000 BCE) and served as the basis for the development of cities during the Copper Age. Age (5900-3200 BC). This last era includes the Ubaid period (c. 5000-4100 BCE), when the first temples (stepped towers known as ziggurats with shrines on top) arose and the emergence of complex art, pottery, and copper tools. an ancient Greek name (meaning “the land between the two rivers”, Tigris and Euphrates) for a region corresponding to present-day Iraq and parts of Iran, Syria and Turkey. It is considered the “cradle of civilization” for many inventions and innovations that first appeared here c. 10,000 BC until the 7th century AD.

In the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period, humans gradually moved from a hunter-gatherer paradigm to an agrarian one, forming seasonal communities that became permanent during the Ceramic Neolithic (c. 7000 BCE) and served as the basis for the development of cities during the Copper Age. Age (5900-3200 BC). This last era includes the Ubaid period (c. 5000–4100 BCE), which saw the rise of the first temples (stepped towers known as ziggurats with shrines on top) and the creation of complex art, pottery, and the production of copper tools.

Be it its geographic location or its fertile soil thanks to the silt deposited year after year by the two rivers the civilization had every reason to grow at a steady rate. Flooding was a problem yes but not something which could not be tacked by the advancing Mesopotamians. They developed a very good network of irrigation which made them utilize not only the abundant supply of water but also tended to reduce the impact of flooding.

Almost every other historian regards Mesopotamia as the cradle of civilization. You might find it interesting to know that it was not merely one civilization which mushroomed in this region. In fact there was quite many a civilization which owes its origins to this region. A simple example should suffice.

The area housed the civilizations of Assyrian, Babylonian, Akkadian and the Sumer empires in the Bronze Age. Likewise it again housed the civilizations of the Neo-Babylonian and the Neo-Assyrian empires in the Iron Age. This is just a small example of the vast number of empires which grew in this river basin.

The civilization is also seen as the first food forward in urbanizing the world. Be it the art and architecture of Mesopotamia or the inventions and literature everything seems to have a taste of urbanization. The finding of a set of written laws referred to as the laws of Hammurabi further strengthens this claim. The laws believed in equality and were set to providing individuals a government which would believe in fundamental rights. There were many loopholes in this code as it was perhaps only a judicial thinking of a ruler but for that time it can be easily compared to our current constitutions.

The raw material that embodies Mesopotamian civilization is clay: in its almost entirely adobe architecture and in the abundance and variety of clay figurines and ceramic artefacts, Mesopotamia bears the stamp of clay like no other civilization and nowhere else in the world Mesopotamia and the areas over which its influence was extended , clay was used as a writing medium. Phrases such as cuneiform civilization, cuneiform literature, and cuneiform law can only be used where people had the idea to use soft clay not only for bricks and jars and for the stoppers of canning jars that could be stamped with a seal as a sign of ownership, but also as a means for impressed signs to which established meanings were assigned—an intellectual achievement that amounted to nothing less than the invention of writing.

The questions about what the ancient Mesopotamian civilization did and failed to do, how it influenced its neighbors and successors, and what its legacy passed on, are asked from the perspective of modern civilization and are partly colored by ethical overtones, so the answers can only be relative. Modern scholars assume the ability to estimate the sum of “ancient Mesopotamian civilization”; but since the publication of the Assyriologist Benn Landsberger’s article on “Die Eigenbegrifflichkeit der babylonischen Welt” (1926; “The Distinctive Conceptuality of the Babylonian World”), it has become almost commonplace to call attention to the need to look to antiquity. Mesopotamia and its civilization as a separate entity.

The world of mathematics and astronomy owes much to the Babylonians—for example, the six-fold system for calculating time and angles, which is still practical because of the multiple divisibility of the number 60; Greek day 12 “two hours”; and the zodiac and its sign. In many cases, however, the origins and routes of borrowing are unclear, as is the case with the problem of the survival of ancient Mesopotamian legal theory. The success of civilization itself can be expressed in terms of its best points – moral, aesthetic, scientific, and last but not least, literary. Legal theory flourished and was soon elaborated and expressed in several collections of legal decisions, the so-called codes, the most famous of which is the Code of Hammurabi. In these codices, the ruler’s concern for the weak, the widow and the orphan reappears – although sometimes these phrases were unfortunately only literary clichés. The aesthetics of art are too subjective to be judged in absolute terms, yet some highlights stand out above others, notably Uruk IV art, Akkadian period seal carving, and Ashurbanipal relief sculpture. However, there is nothing in Mesopotamia to match the sophistication of Egyptian art. A science that the Mesopotamians had of a kind, though not in the sense of Greek science. The aesthetics of art are too subjective to be evaluated in absolute terms, yet certain highlights stand out above others, most notably the art of Uruk. IV, a seal engraving from the Akkadian period and a relief sculpture of Ashurbanipal. However, there is nothing in Mesopotamia to match the sophistication of Egyptian art. Science that the Mesopotamians had, of a sort, though not in the sense of Greek science. From its beginnings in Sumer before the mid-3rd millennium BCE, Mesopotamian science was characterized by endless, meticulous enumeration and ordering into columns and rows, with the ultimate ideal of including all things in the world, but without the desire or ability to synthesize and reduce material to a system. No single general scientific law has been found, and rarely has the use of analogy been found. Nevertheless, it remains a highly commendable achievement that the Pythagorean law (that the sum of the squares of the two shorter sides of a right triangle is equal to the square of the longest side), although never formulated, was applied as early as the 18th century BC. Technical achievements were perfected in the construction of ziggurats (temple towers resembling pyramids), with their enormous volume, and in irrigation, both in practical execution and in theoretical calculations. At the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, an artificial stone often considered a precursor to concrete was used in Uruk (160 miles south-southeast of modern Baghdad), but the secret of its manufacture was apparently lost in the years that followed.

Writing permeated all aspects of life and gave rise to a highly developed bureaucracy—one of the most tenacious legacies of the ancient Near East. To manage huge estates, in which, for example, in the 3rd Dynasty of Ur it was not unusual to prepare accounts for thousands of cattle or tens of thousands of bundles of reeds, required remarkable organizational skills. Similar data are documented in Ebla three centuries earlier.

Above all, the literature of Mesopotamia is one of its finest cultural achievements. Although there are many modern anthologies and Chrestomathia (compilations of useful learning), with translations and paraphrases of Mesopotamian literature, as well as attempts to write its history, “cuneiform literature” cannot really be said to have been resurrected to the extent it deserves. There are partly practical reasons for this: many clay tablets have survived only in a fragmentary state and no duplicates have yet been discovered to restore the texts, so there are still large gaps. Another reason is the lack of knowledge of languages: lack of vocabulary and grammar difficulties in Sumerian. Consequently, it will take another generation of Assyriologists before the great myths, epics, laments, hymns, “law codes,” wisdom literature, and pedagogical treatises can be presented in such a way that modern readers can fully appreciate the high level of literary creativity. those times.

Classical and Medieval Views of Mesopotamia; its rediscovery in modern times

Before the first excavations in Mesopotamia, around 1840, nearly 2,000 years passed, during which knowledge of the ancient Near East was derived from only three sources: the Bible, Greek and Roman authors, and excerpts from the writings of Berossus, the Babylonian, who wrote in Greek. Very little more was known in 1800 than in 800 AD, although these sources served to stimulate the imaginations of poets and artists, right up to Sardanapalus (1821) by the 19th-century English poet Lord Byron.

Apart from the construction of the Tower of Babel, the Hebrew Bible mentions Mesopotamia only in those historical contexts in which Assyrian and Babylonian kings influenced the course of events in Israel and Judah: notably Tiglathpilesar III, Shalmaneser V and Sennacherib, with their policies of deportation, and the Babylonian exile instituted Nebuchadrezza.

Ancient Mesopotamia images are available all over the internet and also in many published books by famous historians across the globe. You can gain a big deal from watching these images as a picture indeed is equivalent to a 1000 words.